Joyce/Ware: Finding James Joyce in Chris Ware’s Rusty Brown

On occasion, I like to write an essay on an esoteric topic. This is one of those occasions.

Portrait of the artist Chris Ware with a young man (me). Apologies for waiting three years to read your book.

In November of 2019, I attended Comic Arts Brooklyn, in part to attend a lecture by Art Spiegelman (Maus), Françoise Mouly (Raw) and Chris Ware (Jimmy Corrigan). Afterwards, I joined the line to have items signed by Mr. Ware (or Chris, as I presume his friends call him). We had a pleasant conversation, which I extended by also purchasing a copy of his newest novel, Rusty Brown. Based solely on what I’d heard them discuss in the panel, specifically that part of the book follows the actions of multiple characters over the span of a single day, I mentioned to Mr. Ware that it reminded me of James Joyce’s novel Ulysses, one of my favorite books. He confirmed that Joyce was one of his favorite authors and had influenced Rusty Brown, building in me a sense of genuine connection with someone I held in high esteem. Leaving the signing with his latest work in hand, I was eager to dig into the graphic novel. But when I returned home, I put the novel on a shelf where it remained unopened for three years.

Completing a book after such a long delay was odd for me, as I try to keep my book queue tidy, but it reminded me of an earlier event from years prior. In 2006, I was gifted a copy of James Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, and I didn’t read it until 2012. That delay was due more to intimidation (Portrait’s reputation preceded it) than laziness, but the parallel resonated with me, especially now that I’ve read Joyce’s four major works and Ware’s three (he’s still got time to catch up).

Though it’s been several years since reading these books, aspects of them remain fresh in my mind, especially when they are recalled in another piece of media. Anytime a work is compared to Ulysses I take interest, though usually the similarity is based on one of three superficial reasons:

It has a complexity that is hard to discern

It uses ‘stream of consciousness’ style in its language

It is long

These points are obscenely reductive, but the novel is notorious for being well known and rarely read. Being a shameless ‘Joyce snob’, these kinds of comparisons irk me to my snobby core and demand scrutiny. Typically, the link is shallow, though there are exceptions. The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway has been called “the Ulysses of Concept Albums” by many. This declaration had a major influence on my decision to illustrate the album so I could analyze the work and draw my own conclusion. And although I don’t think Peter Gabriel made conscious allusions to Joyce, there is a similar level of thought and care put into the concept and the album’s structure. Thus, I was happy to conclude that the parallel is genuine and the Lamb is awesome.

When it was published in 2019, many reviewers noted the connection between Rusty Brown and Ulysses, specifically in its extended prologue (as did I, as recounted in paragraph one). Having now actually read the damn thing, I was able to certify that the comparison is done with genuine care and Ware clearly has a deep knowledge of Ulysses. However, what surprised me and led me to write this essay was the trove of other links I noted between the Rusty Brown and Joyce’s novels. In finding little scholarship that addresses this beyond the aforementioned prologue/Ulysses connection, I felt compelled to address it myself, in the hope of inspiring others to give Rusty Brown the academic analysis it so obviously deserves.

This is a problem I’ve found across scholarship of comic books, with analysis routinely skimming the surface of narratives to focus on superficial aspects. The medium of sequential art (comics/graphic novels) has always struggled to be taken seriously, mostly due to its intrinsic ties to superheroes and other pop genres seen as ‘childish’ or ‘lowbrow’. Video games face a similar issue, as evident by the constant stream of op-ed pieces asking whether they even qualify as a true artistic medium (spoiler: of course they do). One could argue it’s because these are relatively recent mediums, but comics were not invented when superheroes became popular in the 1930s. The medium itself has been around for far longer, with its earliest examples in the 1800s placing it around the invention of film, a medium that has no issues being taken seriously (except for animation, but that’s a topic for another essay). If one expands the definition of sequential art to include any sequence of images that, when taken together, reveal a larger narrative meaning, one can make a valid argument that comics are as old as cave paintings. Scholarship of the origin of comics is thus murky territory, though some have made valiant efforts to codify it. One such person is none other than Mr. Ware, who penned an essay on the topic in 2008 (link, well worth a read).

Although there is a rich history of comics addressing mature topics and achieving incredible results, this struggle for legitimacy persists and scholarship remains lacking in key areas. But I have hope that this trend can be corrected if people are willing to give these works a closer look, and by chance there is a great parallel in the writings of James Joyce. Though it’s seen as haughty art now, Ulysses faced a similar struggle for legitimacy when it was first published. Its frank depiction of taboo topics had it labelled as pornographic and banned for many years in countries around the world. Even amongst Joyce’s peers, his work had its detractors, mainly due to its focus on lower-class characters. At the time, many felt that a proper novel could only focus on upper-class people, and Joyce was wasting his talent on people of no importance. Virginia Wolff was a critic of the novel for these reasons, (though judging by how closely she cribbed it for her cheap imitation, Mrs. Dalloway, perhaps she was projecting a bit).

What follows is an analysis of other links I noted between Rusty Brown and Joyce’s body of work. This is not a comprehensive list, but a sample serving to argue that Rusty Brown (and Ware’s other works [and comics in general]) are worthy of a higher level of analysis and scholarship. In my analysis there will be some plot discussion, so if you are worried about spoilers I suggest reading the books first (they’re very good). Another thing to keep in mind is that Rusty Brown is a collection of comics created over a twenty-year period that add up to half a graphic novel (the book literally ends with the word “Intermission”). Ware intends to produce a part two at some point, so it’s possible some of my analysis will have to be revised/expanded whenever this concluding volume is released. But since that likely won’t be for a long time, my essay will work within the bounds of what we have and treat it as a complete work. As it exists today, Rusty Brown is divided into four sections: Prologue, Woody Brown, Jason Lint, and Joanne Cole. Each contains ample implicit and explicit references to Joyce.

Prologue

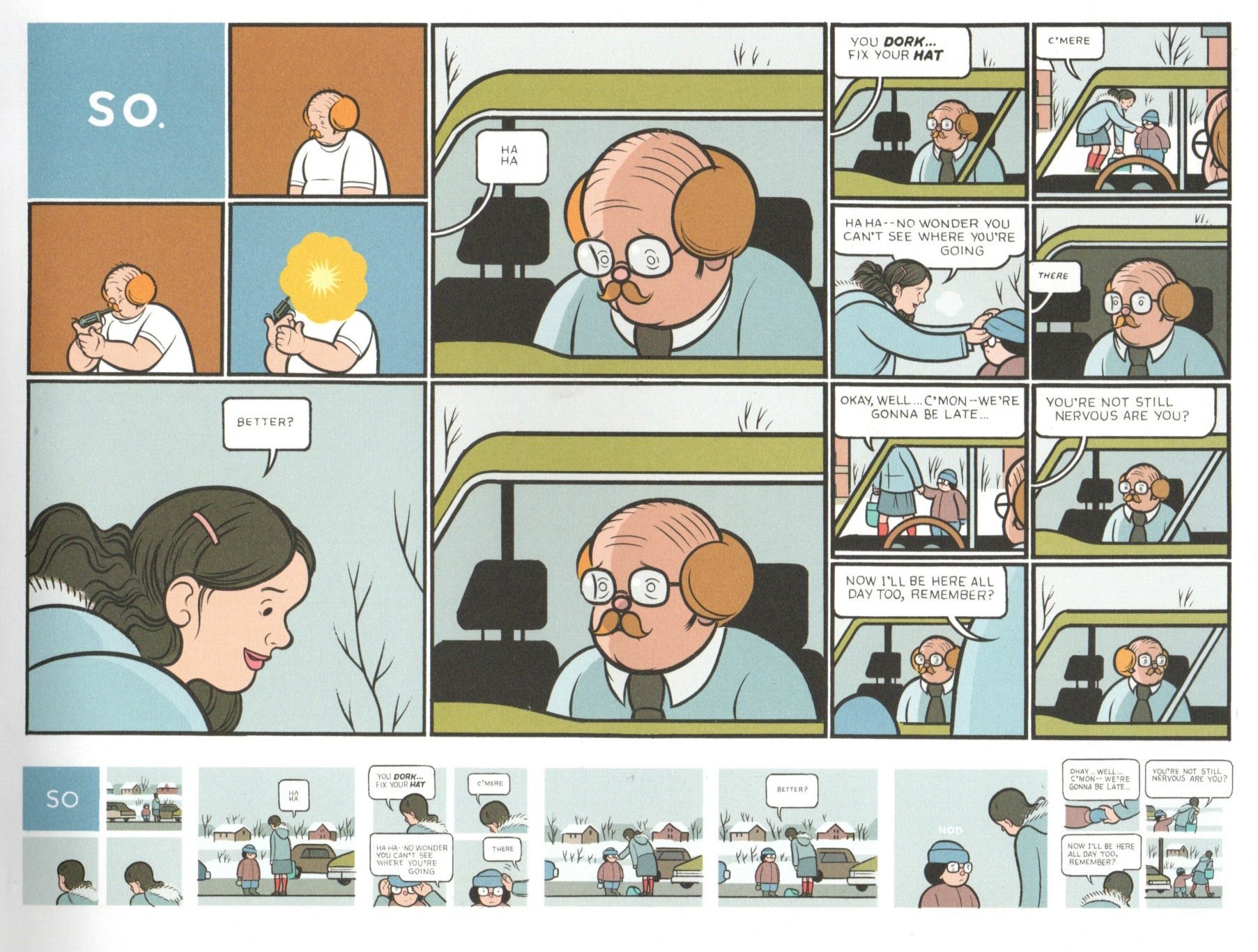

Prologue scene showing the uneven panel structure of A and B stories. Here, they coincide from different character perspectives, with the shared word ‘So.” signifying synchronization. From “Rusty Brown”.

The Prologue is an extended sequence that follows the actions of numerous characters across a single day. It serves to introduce major players within the story and its concept is the clearest reference to Ulysses, which similarly takes place on a single day and follows many individuals. Just as Ulysses morphs its writing style and structure with each passing chapter, so too does the Prologue evolve through changes to its panel layout and narrative focus.

The Prologue’s first half follows a panel hierarchy where approximately 4/5ths of the page focus on an A story and the bottom fifth focuses on a B story. This expresses an advantage sequential art has over written text, allowing for multiple images to display on a single page and easily build a contrast in the reader’s mind. Simultaneity plays a large role in Ulysses but is driven by the constraints of written language. At first, the novel continues the story of Stephen Dedalus (protagonist of Portrait), following him in the early hours of a day in June. But after three chapters, the story shifts focus to a new character, Leopold Bloom, beginning with what he was doing in parallel to Dedalus during the same hours of the same day in June. The reader is oriented to this simultaneous action by mentions of time of day, the angle of the sun, the weather, and other means, but it takes some effort to keep track of it all. Meanwhile, Ware simply needs to show two actions on the same page to denote they happen at the same time. Since the Prologue’s A and B are given uneven real estate on the page, the A story inherently feels more important. When Ware swaps the subjects of the A and B plots partway through, it feels significant to the reader. This recalls later chapters of Ulysses, where Bloom is put into the background so that Dedalus or another character can steal the spotlight for a short while.

The Prologue’s second half ditches this rigid structure for a more traditional page layout grid, but in doing so it expands the focus of the story to encompass even more characters. This recalls Ulysses’ tenth chapter, Wandering Rocks, where there is no singular focus as perspective shifts between numerous characters around the city of Dublin. On first read, it’s not immediately clear who will play a larger role in the story later, since all get similar footing. Likewise, the Prologue gives moments of focus to a range of characters at the same school. Rusty Brown, his father Woody, bully Jason Lint, new students Alice and Chalky White, teachers Joanne Cole and Mr. Ware, all are given some moment in the spotlight. Just as Wandering Rocks presents a full picture of the system of interactions that make up Joyce’s Dublin, the Prologue reveals a network of players all tethered to the focal point that is Rusty Brown, a sad and strange boy who will play only a minor role in the stories to come. Rusty, in essence, is Ware’s Dublin, linking the rest of the characters in unexpected ways.

In the list of characters above, you may have noticed one is called ‘Mr. Ware’. Just as Stephen Dedalus is known to be an exaggerated stand-in for his author, this character plays a humorous foil to his namesake. While the author Chris Ware is by all accounts a lovely person and talented artist, the character Mr. Ware is an amoral art teacher not above smoking pot with students and sneaking a peek up their skirts. In the brief window we get into his thoughts on his art, author Chris Ware does an excellent job lampooning the excessive meaning and symbolism artists will often attribute to their works, using many words to say very little.

Many authors, concerned with their reputation, would likely make their stand-ins seem noble or at least pleasant. Joyce and Ware have both forgone this, presenting instead a self-immolation that showcases their similar senses of humor and ability to make themselves the butt of the joke. Although Dedalus is intelligent, he is also depicted as a moody spendthrift and, for lack of a better word, an asshole. His abundant education is contrasted with his self-destructive drinking, with little art to show for being the subject of the Portrait of the Artist. While the reader wants Dedalus to reform and succeed, as Joyce casts him in a sympathetic light, Mr. Ware is not given such pathos. Instead, we are more than happy to move onto someone else.

The perverted nature of Mr. Ware, as well as his colleague Woody Brown, focuses on Alice White, possibly since she is a new student and therefore novel. It is very uncomfortable to read, but also presents another link between Ware and Joyce, since it parallels the controversial Nausicaa episode of Ulysses. In this chapter, Bloom encounters the young Gerty MacDowell, who arouses him to the point of completion. But while Gerty’s inner thoughts express a desire to be seen as beautiful by men and admired (a response to her own insecurities and having recently been dumped), Alice wants nothing of the sort, finding her new school unpleasant and missing her old friends. Though both have nuance, Alice’s portrait feels more realistic, as anyone that has been a new student at an unfamiliar school may recall how difficult it can be. To add to that the unwanted attention of peers and teachers makes the Prologue a stimulating and challenging read, a feeling that extends to later sections of Rusty Brown as well. Masturbation plays a role in life, and thus it plays a role in Ulysses. Bloom and Dedalus both masturbate at different times (on the same strand, by chance) for different reasons, and characters in Rusty Brown are shown to do so as well. Although the topic can be taboo, these are works that do not shy away from depicting the world as it is, a feature that serves as another link between the two authors.

Woody Brown

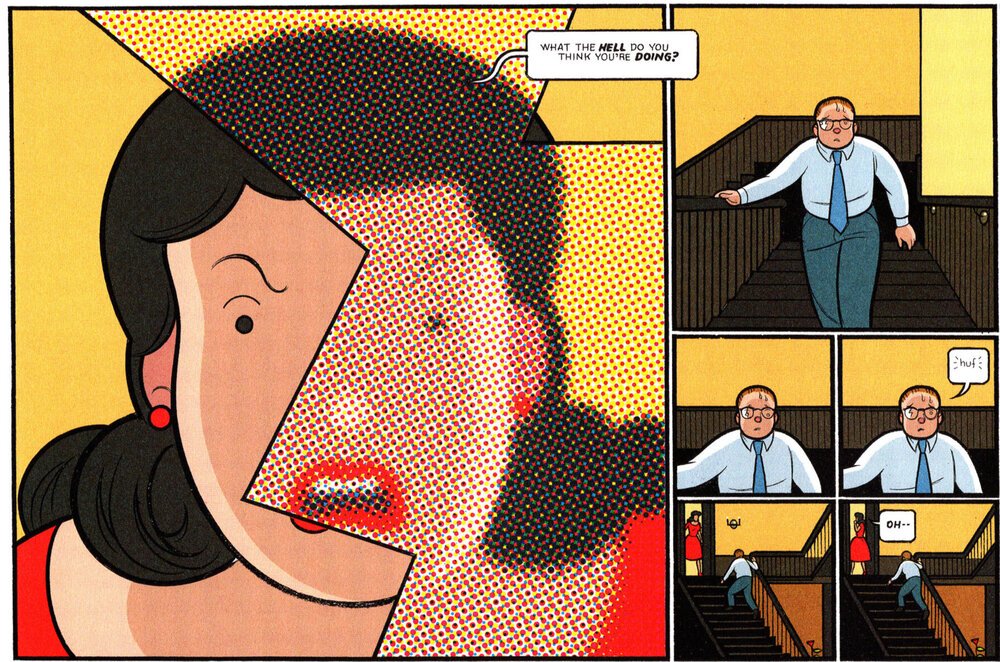

Woody Brown scene showing the world through his broken glasses. For fun, trying viewing this from far away to see the full effect of the Pointillistic style. From “Rusty Brown.”

The next section, Woody Brown, has connections to multiple works of Joyce and his character Stephen Dedalus. Woody Brown is divided mostly between an interpolated science fiction story (written by the character) and an extended flashback about the toxic relationship that led to the story’s creation, with the conclusion showing Woody as he masturbates in recollection of the events from decades earlier. Each of these divisions has parallels within Joyce’s Dedalus, with some more explicit than others.

The sci-fi story’s insertion is abrupt, halting the flow of the Prologue and forcing readers to reassess the scope of the book's narrative. Similarly, the third-person narrative of Portrait is interrupted by a poem (composed by Dedalus) and the novel concludes in an epistolary style (diary entries also written by Dedalus). These changes in perspective and style can disorient a reader, but in the context of making a story about a creative person it is vital to show examples of their creations. The surprising success of the sci-fi story, as recounted by Woody (he won a medal!), bears a striking resemblance to Dedalus winning a cash prize at school, only to later squander it on gifts and prostitutes. Dedalus’ early success was inspired by real events in Joyce’s life, specifically winning a contest for English composition while at boarding school. For all three, the hope that comes with success is followed by a long fallow period, showcasing the heaven and hell of trying to live as an artist. Woody took on teaching to make ends meet, as does Dedalus at the start of Ulysses and as did Joyce in real life. Perhaps this is a common enough pattern to be called a coincidence, but the resemblance is uncanny.

The characters within the sci-fi story are inspired by the extended flashback we get next, namely a toxic relationship between a young Woody and his older coworker at a local newspaper. There is a pity to seeing Woody’s naive sense of love permeate what is obviously an unhealthy situation, and the steps he tries to take in treating it like a romance inevitably ends in heartbreak. In one of the saddest scenes, his lover offers Woody one hundred dollars to stay away from her, a buy off that a tearful Woody refuses. This event is followed by a pattern of forgiveness, sex, and rejection that is clearly unfair to Woody, who is being used by his lover like an object. Contrast this to Dedalus’ craving for prostitutes and it’s clear that Ware has made a clever inversion of this power dynamic. The exchange of money may happen in opposite directions, but both events veer the character off their intended path. Woody loses his job while Dedalus is scared straight on a Catholic retreat. And yet, out of this pain comes Woody’s sci-fi story and Dedalus’ poetry.

In Woody’s flashback, there is also an explicit connection to Dedalus’ story in Ulysses. During Woody’s period of romantic upheaval, he goes for a long while without his glasses (they break and then his replacement pair is also humorously broken). Similarly, near the end of Ulysses it is revealed that Dedalus has gone the entire day without his spectacles, which were broken the day before. Ware portrays this altered viewpoint through a unique Pointillistic style, while Joyce uses impressionistic language to describe what Dedalus is seeing as he ponders the “ineluctable modality of the visible… thought through my eyes.” Walking around without glasses can feel liberating, softening the outside world to focus on an inner one, but also dangerous, since you are susceptible to bump into things. That both these characters experience this speaks to the question of what is real, a question asked by all artists.

The concluding part of Woody’s story brings him back to the present, tracing how he met his wife, got a job teaching, bought a house, and had a kid. While for many this would be a happy ending, for Woody it is anything but, and his days are spent longing for the woman that broke his heart. It is frustrating to have a character that seems ungrateful for their life, but it deepens the realism of the story. And while his flashback section parallels Dedalus, this portion recalls Bloom, who is of a similar age with a wife and daughter. Although Bloom thinks better of his home life than Woody, he likewise opines for an earlier time when he and his wife Molly were closer. This marital wedge reaches its apex when Bloom discovers Molly is having an affair, a path that feels probable for Woody to take in a future installment of the story. Both stories speak to the challenges of long-term relationships and the poison of misplaced nostalgia, but where the Blooms give an optimistic sense that things may work out eventually, the Browns feel doomed to fail.

Jason Lint

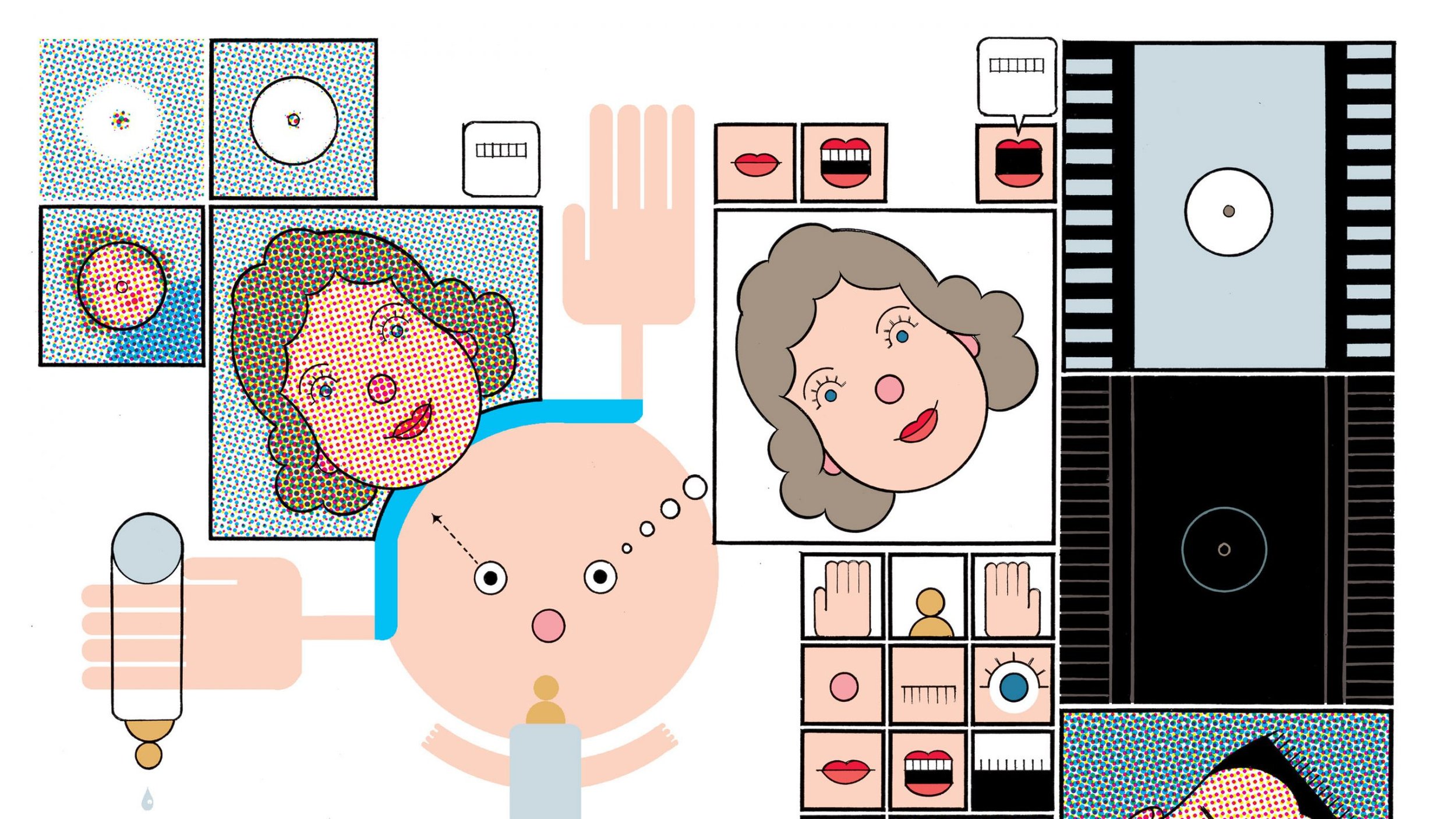

Jason Lint scene exploring child development in artistic form, as Joyce does in the writing style of Portrait. From “Rusty Brown.”

The third section of Rusty Brown follows the life of Jason Lint from birth to death, one year per page. Although Lint is a far cry from the meek Woody, both relate to Dedalus in unique fashion. Links between Lint and Dedalus occur both formally and thematically. The artwork of Lint matures alongside the character, beginning in abstract and simplistic diagrams before settling into Ware’s signature style. This development mimics the writing of Portrait, which begins in a childlike vocabulary and grows alongside Dedalus into a complex prose. Lint benefits from being able to portray the entire cycle of life, while Portrait ends with Dedalus in his early twenties. However, this shorter period can be seen as a full cycle, from Dedalus’ first birth as a person to his figurative death/second birth as an artist.

Structurally, Lint’s story is a chiasmus, with the second half’s order a mirror of the first half. This puts a focus on the midpoint and adds to the cyclical nature of the birth/death it depicts. Likewise, Hugh Kenner identified Portrait’s structure as a chiasmus, with its five parts divided in a mirrored fashion. Chiasmus holds a larger significance in comic book panel layout, with a famous example being the graphic novel Watchmen’s fifth chapter, “Fearful Symmetry.” It also is a rhetorical figure used in a poem Dedalus composes. Thematically, the structure of a chiasmus lends a significance to the mirror point. For both Lint and Dedalus, the middle of their stories revolves around a religious revelation and a promise to “be good;” a metaphorical midlife crisis for each character. Both characters eventually fall from this point of stability, but where Dedalus charts a new path as an artist (albeit one that stumbles into writer’s block), Lint reverts to previous vices and instant gratifications.

The self-destructive tendencies of both characters can be traced to their relationships with their parents. Although Dedalus’ mother plays a small role in Portrait, she is pivotal to his motivations in Ulysses, haunting him with the guilt that he refused to grant her dying wish. Lint’s mother, who passes when he is young, similarly haunts his thoughts and is a major catalyst for his development from a sensitive, well-behaved boy into a problem child. The strained relationship both characters have with their drunken fathers is likewise a large factor in each story, with each eventually repeating their father’s mistakes, despite their best efforts. All of this makes clear that Ware has a deep understanding of Joyce’s works and recalls them in nuanced forms.

Joanne Cole

Scene from Joanne Cole. The absence of text evokes her introverted lifestyle and focus on her banjo hobby. From “Rusty Brown.”

For the last section of Rusty Brown, the narrative follows Joanne Cole, a black teacher (later administrator) in Rusty’s overtly white school system. The reader witnesses her professional and personal struggles in a manner that recalls Joyce’s Leopold Bloom. Unlike previous sections that had rigid structure, Cole’s narrative jumps between time periods in abrupt fashion, doling out to the reader a curated string of clues as they seek to understand her character and motivations. Instead of showing events, Ware identifies patterns, giving the work a stream of consciousness feeling. It's unclear if these shifts are Cole’s personal recollections or an omniscient ordering, but regardless the effect is akin to Bloom’s mindset in Ulysses. Through internal and external stimuli, Bloom’s mind bounces from topic to topic in a winding trail with little regard for whether a reader can follow it. In piecemeal fashion, we learn about each character’s history and come to sympathize with their situations.

Like Bloom, Cole is a complex person with idiosyncratic interests. An avid banjo nerd, she finds few people within her daily life that share her hobby or can be bothered to put up with it. Likewise, Bloom is noted to have few things in common with his acquaintances, spending his time pondering the kinds of questions few would bother to ask, such as whether ancient sculptors bothered to depict the anus in their figurative nudes. Thought Bloom seems content to live a relatively solitary life, often oblivious to the impression others have of him, Cole seems more desperate for connection, especially as her home life caring for her elderly mother deteriorates.

Despite their flaws, both characters are undoubtably good people, making their woes hit harder for compassionate readers. Both experience persecution throughout their lives, Cole as a black woman and Bloom as a Jewish man, depicted in manners that feel unfortunately realistic (speaking from experience as a Jewish person myself). Cole’s flashbacks to growing up in the 1950’s/60’s show many examples of the racist behavior one would expect from that time, but to all of these she turns the other cheek. Although the racism becomes subtler as she gets older, it never fully goes away. Likewise, Bloom faces different levels of antisemitism throughout Ulysses, ranging from stereotyping to aggressive beratement. After a particularly nasty encounter, the book forgoes its usual pace of one hour per chapter to jump ahead several in a single bound. This makes one feel as though Bloom has hidden from the novel itself, needing time to recover from the unfortunate incident.

With Cole’s flashbacks to her childhood, there is a rare instance where a white person does not act bigoted towards her. The person is an older man dressed in a dark suit and wide brimmed hat, tipping it kindly instead of berating her for not moving out of his way. This outfit bears a resemblance to the Hasidic Jewish style but could even be a more direct reference to Bloom, who is wearing a similar outfit during the events of Ulysses to attend a funeral. The action of one minority showing kindness towards another recalls a major theme of Ulysses, with Joyce drawing a connection between the plight of Jewish people and that of Irish people (while also noting the irony of rampant antisemitism amongst the denizens of Dublin).

A final aspect that links the two characters is the loss of a child. Both do not outwardly discuss this trauma, but inwardly it motivates their actions and peculiarities. During this journey, each seeks substitutes for their loss, with Bloom finding some semblance in Dedalus and Cole in a former student. The resolution of their pain is vastly different, but by the end of each story both find a similar level of acceptance and closure.

Conclusion

These threads between Ware and Joyce speak to the depth of the former’s influences, but it’s important to note that other subjects may be revealed with further analysis. For example, in the writing of this essay I made the realization that Rusty Brown’s structure and narrative also recalls Faulkner’s novel The Sound and The Fury. Faulkner’s novel is divided into four parts, each based on a member of the Compson family. The first is from the perspective of intellectually disabled Benjy, who recalls the man-child Rusty Brown grows up to be. The second part focuses on Benjy’s brother Quinten, who like Woody is intelligent and prone to depression. The third part follows Jason, whose brutish nature is a close fit to Lint. The final part is broader in its scope, but mainly follows Dilsey, one of the Compson’s black servants. Like Cole, Dilsey’s faith is the essence of her endurance.

Authors like Ware have the capacity to draw inspiration from numerous sources, so it is likely that there are even more links one could draw between their works and the literary canon. As mentioned previously, this essay is not a comprehensive list, but rather a sampling to show how much can be drawn from even a fairly close reading of Ware’s graphic novels. The Comic Arts Brooklyn that I attended in 2019 has so far been the last, with subsequent plans cancelled due to the ongoing pandemic. Though this is unfortunate, it adds to the mystique that Rusty Brown holds for me and contributed to my desire to write this article and preserve its sentimental importance. Such personal motivation is pivotal to inspiration, and I’m sure Mr. Ware has plenty of similar stories about reading Joyce or other authors. But unless people start looking into these things and asking about them, we’ll never know the full story. I hope that with this essay, others may be inspired to give a close read to deserving works in the sequential art medium (and not wait years to get around to reading them like I did [apologies to Mr. Ware]).